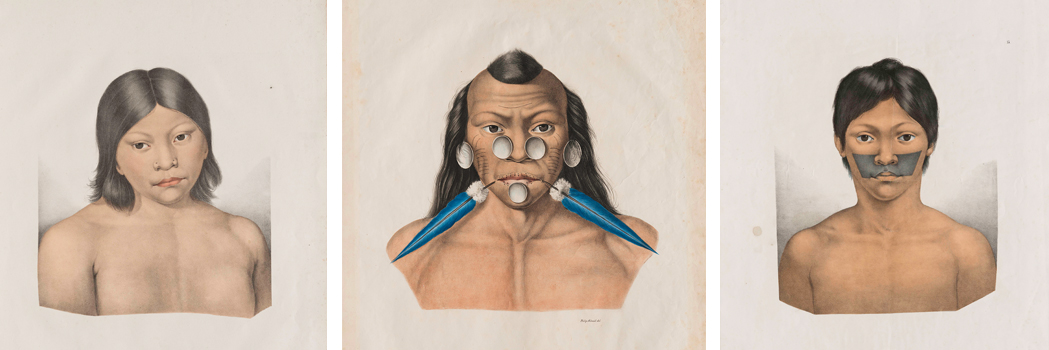

Índios Miranha, Iuri e Muxuruna, do álbum Viagem ao Brasil, de Spix e Martius (1823). Foto: Edouard Fraipont

.01

Brasiliana: art tells the history of Brazil

Above all, this is an art exhibition. Art either produced in Brazil or about Brazil itself: by domestic or foreign artists, tackling the issues of our country.

This museum is closely linked to the history of the country, and the display unfurls over five centuries. While the chronology is important, it is the images themselves that take centre stage, whether printed, drawn, engraved, painted in oils or in watercolours. Paper is the principal support for most of the works, but there are also a range of paintings on canvas, sculptures and objets d'art, including coins that were once legal tender in Brazil, bearing finely chiselled images of monarchs and scenes.

However, this is not an exhibition addressing Brazil's history, although this very history is evoked everywhere. It is a display of images and objects left by many of the most outstanding artists in Brazil since the discovery.

No artefacts have come down to us of the native population found by Cabral, only engravings of Indians as imagined by the Europeans. The museum houses original works by Frans Post and Albert Eckhout, among the first European painters brought to the New World by Maurice of Nassau, as well as significant engravings based on their drawings. The following period (in which Brazil was concealed by the Portuguese crown for 150 years until the arrival of Dom João VI) reveals virtually anonymous artists—with one notable exception, the greatest among them, Aleijadinho, one of whose major works the museum owns. That was a period of large coins reflecting the prosperity flowing towards Portugal from the gold of Minas Gerais, as well as an era marked by the poetry of the Minas "Inconfidentes" (rebels), the heroes of a time when Minas Gerais lay at the very heart of the attentions of the Metropolis.

After the Portuguese Court arrived in 1808, an eighty-year period, ruled over by three monarchs, began: Dom João VI, Dom Pedro I and Dom Pedro II.

Brazil was flooded by traveling artists and scientists, eager to unveil its mysteries, record its data and bring back its images to Europe. The exhibition seeks to highlight the extraordinary works of these artists who visited the country after 1815. The “roving painters” bequeathed oils, drawings and magnificent engravings to posterity. They had exceptional skills, as the exhibition shows, and tackled important issues.

Rio de Janeiro also took center stage, the gateway to the country: visitors were beguiled by its beauty and depicted it in every possible way. The rich output of images and panoramas of Rio from 1810 to 1850 is particularly well represented in the museum: rarer images or those never shown before were also chosen to make up this group.

The talent of the roaming artists shines through their approach to the grandeur of the landscape, and pins down the focus of this permanent exhibition.

Few foreign artists abandoned Rio to paint the landscapes of the interior, but some did extend the scope of the museum's visual heritage by portraying the provinces. During the Empire, art catering to the demands of the court did not lose its impact just because it was commissioned: the artists' creativity shines through even when the subject-matter is imposed on them.

In any case it was the contemporary issue of slavery, observed daily by foreign and home-bred artists, that outweighed imperial commands. No other theme was so closely associated with the image of Brazil in the nineteenth century than the forced labour of Africans—rivalling the symbolism of cannibalism that had dominated the earlier centuries' imaginings; and slavery was to end only very belatedly in Brazil.

Many lesser wandering artists—such as Rugendas, Debret, Chamberlain and Frond—devoted themselves to depicting the crueller (albeit occasionally joyful) side of life as a slave, as dozens of engravings in this exhibition bear witness; there is also a selection of documents attesting to the intense economic activity of slavery.

We now come to the last room of the museum, comprising mainly twentieth-century works, emphasizing the creativity of the artists and illustrators who took their inspiration from the works of great figures of Brazilian literature.

The exhibition intends to fully display rarely exhibited works of some of Brazil's leading textual artists. There is also room for literary works and documental records evoking the environments in which those artists worked: official nineteenth-century documents and major printed twentieth-century texts, showing the maturity of Brazilian literature, in the footsteps of Machado de Assis.

Olavo Setubal's collection caters to an on-going quest for significant pieces that help shed light on Brazil; however, the main goal of the curators has been to highlight the talent of many less-well-known artists. They deserve to be part of the as-yet uncreated canon of the wealth of Brazilian art over the last one hundred years. The body of images and texts that this collection has mustered, including so many unedited pieces, has hardly been studied, but can now enable a new and more thoroughgoing reflection on the contributions made by the first centuries of Brazilian art. This will undoubtedly help shed new light on many of contemporary art's quandaries and enrich our understanding of Brazil.

Pedro Corrêa do Lago